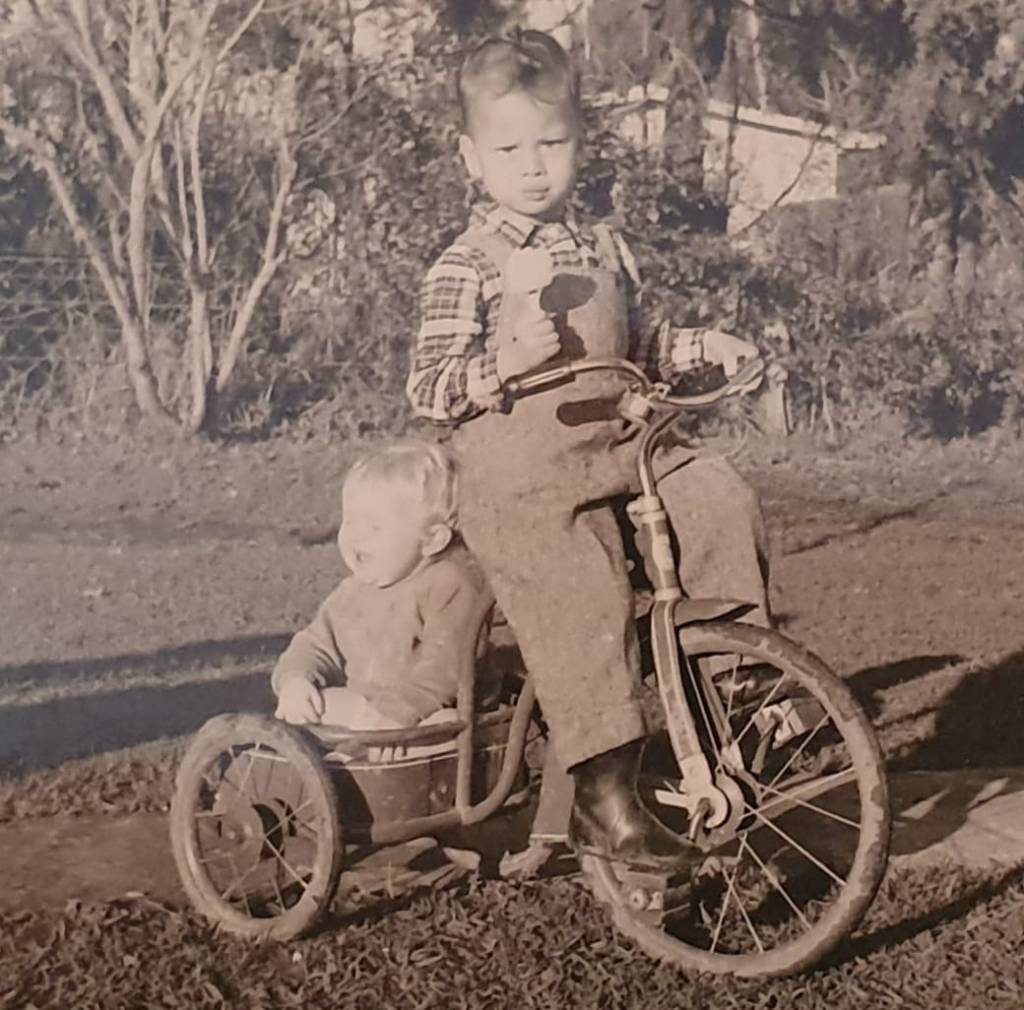

I was born within the cultural boundaries of Te Whakatōhea in the township on the east coast of the North Island of Aotearoa, the picturesque town of Ōpōtiki.

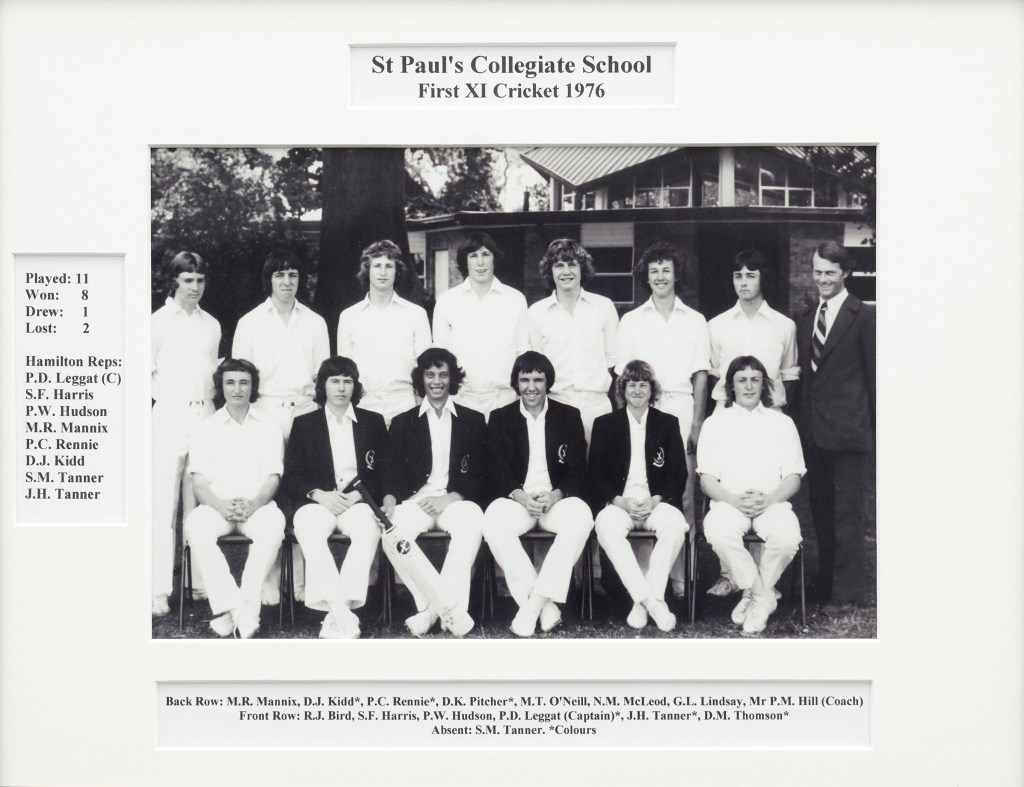

My teenage years saw me leave Ōpōtiki for the ancestral lands of Tainui-Waikato in the pursuit of secondary and tertiary education.

This is migration as we know it.

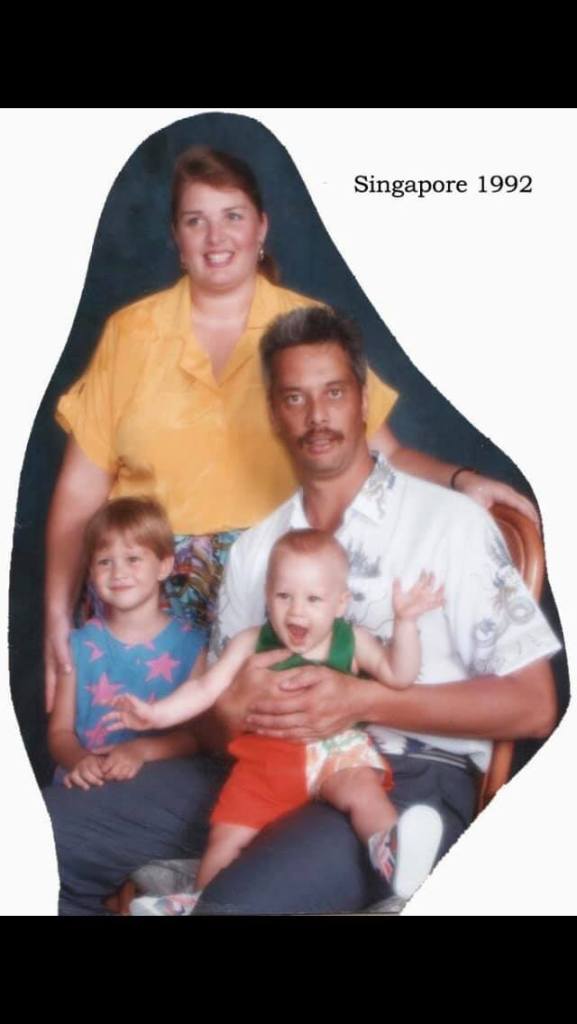

An educational career offered the opportunities for me to travel to other land outside of Aotearoa visiting and living on many Indigenous ancestral lands including Denmark, on the homelands of the Sámi people; on the motherlands of the Indigenous Indians of San Diego County; in Singapore alongside the inheritors and practitioners of Asian cultures; on the ancestral homelands of Auckland, Ngati Whatua, Whakatane, Ngati Awa and now here on the banks of the Whanganui awa, our home located on the shores of Castlecliff beach on the tribal lands of Te Atihaunui a Pāpārangi.

This is migration as we know it.

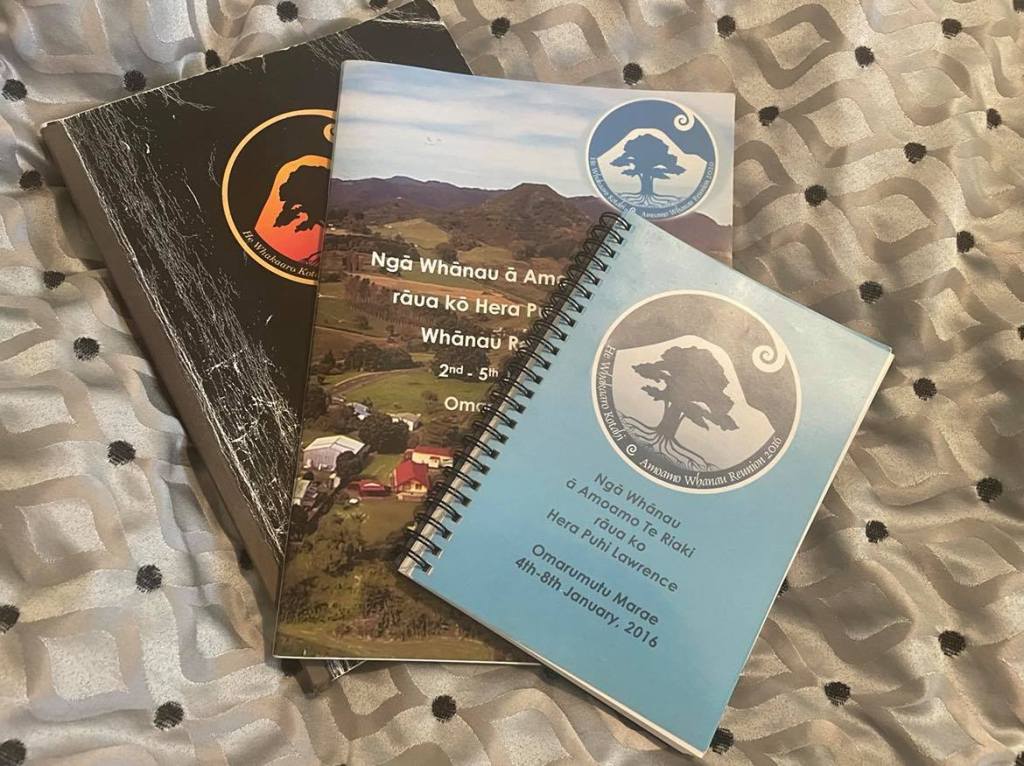

Overseas experiences, possibilities of financial sustainability and bright lights draw me to the overseas cities of Europe, Asia and the United States. My family and I would made the point to return to Te Whakatohea to be with our whānau who lived within the our tribal boundaries and to specifically gather on our marae to attend birthdays, weddings, tangihanga, holidays, and other whānau events spending periods of time connecting and reconnecting with our huge, extended, loud, wonderful whānau. My migrational escapades are not mine alone. Some of my whānau remained on our tribal lands, however, many, like me, built new homes somewhere else, some never to return.

This is migration as we know it.

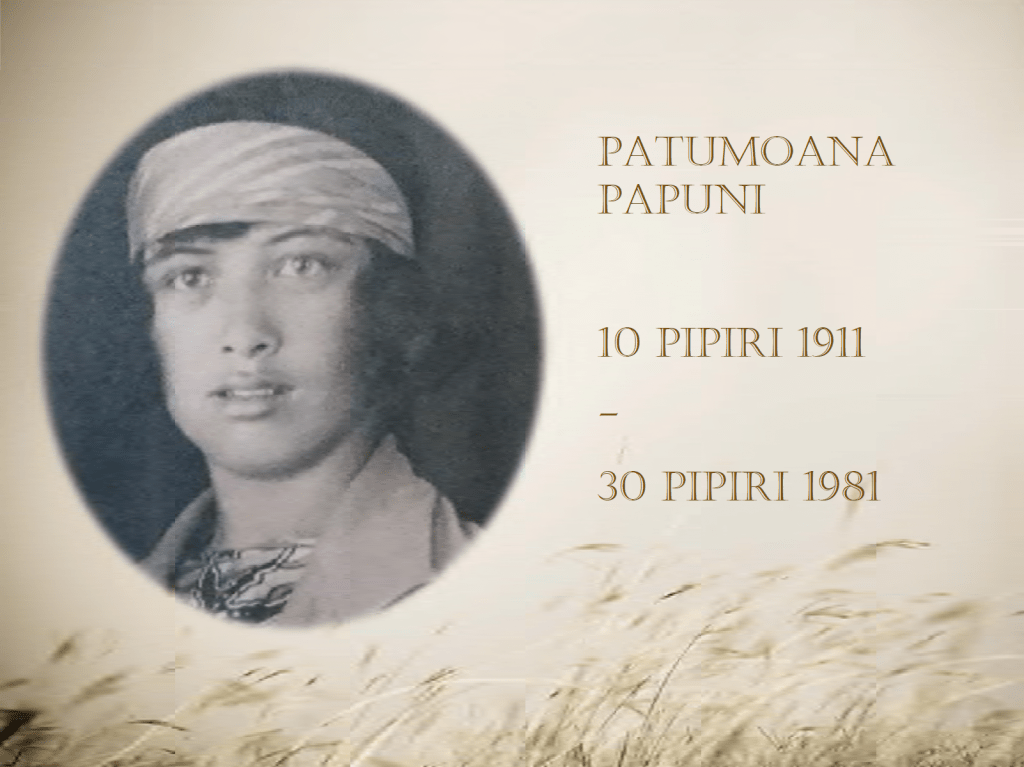

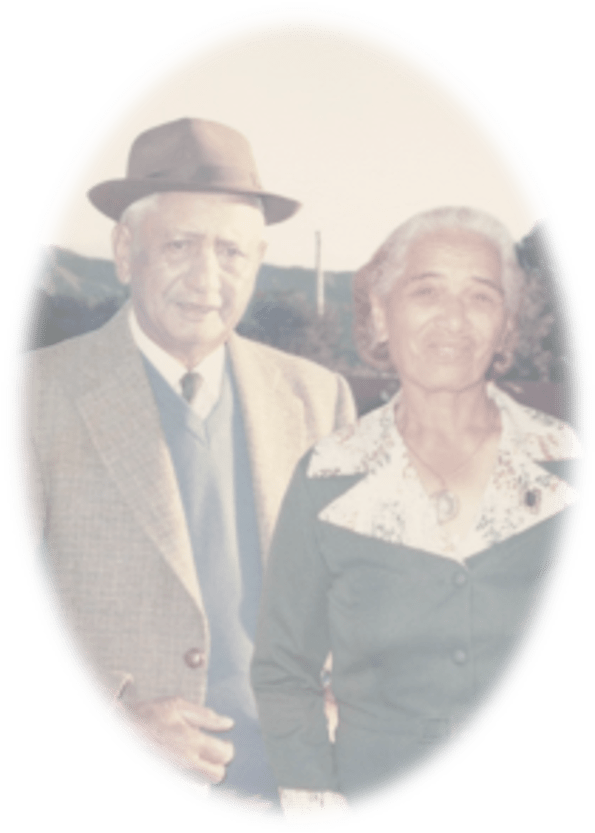

I am a whānau member of Ngā Uri o Patumoana and Raikete Amoamo. A large proportion of my whānau; children, grandchildren, aunties, uncles, cousins, nieces and nephews live away from our tribal homeland of Te Whakatōhea. In fact 83% of our whānau living outside our tribal boundaries of Te Whakatōhea; with 24% of our whānau members living outside Aotearoa.

This is migration as we know it.

My Whānau and I have a unique physical, political and moral status as Māori, as tangatawhenua. This positioning ties us to our iwi, te Whakatōhea and our hapū, Ngati Rua. This institutional standing provides my Whānau and I the potential to support and maintain our Māori identity as descendants of Tūtāmure. My Whānau and me that live outside te Whakatōhea boundaries but inside the seaboards of Aotearoa have the distinct openings to remain connected with ease of access to ‘home’ and local whānau communities in the areas we are living. My Whānau who live in Australia also have a the geographical proximity to Aotearoa which again provides opportunities to retain connections, both through the ease of access to ‘home’ (when covid allows) and with Whānau and Māori communities living in Australia. However, I do worry about my Whānau living in Europe. I will need to talk with my cousin and ask how he and his family feel about their physical, political and moral status as Māori.

This is migration as we know it.